Speed Shifting

Perhaps the biggest initial problem riders have when trying to go faster (especially on a track) is shifting correctly. By that I mean being able to upshift and downshift as quickly as possible without upsetting the chassis. It is all too common to hear horrible noises coming from the transmission as an aspiring performance rider mashes gears with reckless abandon. Even worse is seeing the rear tire chatter as the rider downshifts from a high speed without “rev-matching.”

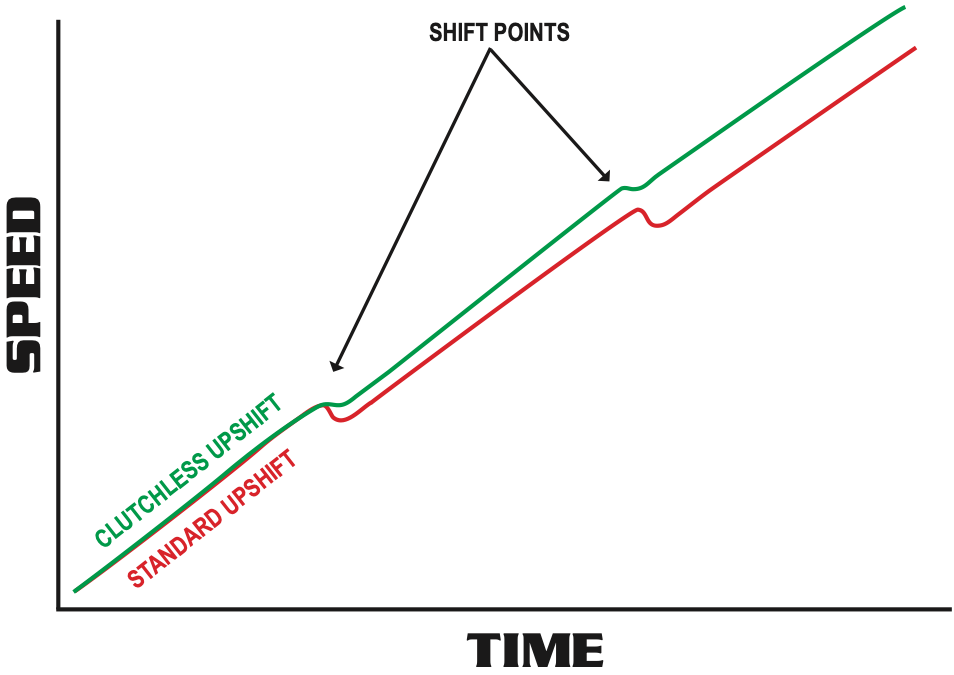

In upshifting the primary goal is to reduce the amount of time that you are not accelerating. As you can see on the graph, the red line shows how you lose speed each time you pull in the clutch and shift, making you vulnerable to vehicles trying to get you're your space.

Ideally, you can minimize acceleration loss by performing clutchless upshifting. For years race bikes have used quick shifters to shift gears without having to close the throttle. Nowadays even some street bikes are starting to come stock with them for upshifting and even downshifting. They work by having a sensor detect movement in the shift linkage from the rider’s foot and then cut the ignition for about 20 milliseconds. This unloads the transmission and allows it to easily shift into the next higher gear. While you may not have a quickshifter on your bike, you can accomplish almost the same result by mimicking the “cutting-power” action with your throttle.

The first step is to make sure the engine is under full load. This means full throttle but not necessarily super-high RPM. The second step is to preload the shifter by putting upwards pressure on the lever but not quite enough to make an upshift. The final step is to quickly roll off and back on the throttle, while simultaneously completing the foot movement to shift. The wrist movement here should be as small and as fast as possible, not unlike blinking an eye.

As you can see on the graph, because of the reduced amount of time that the engine is “disconnected” from the transmission, the bike is able to accelerate quicker. Additionally, passengers will hear, but not necessarily feel the shifts, which also prevents the helmet bonks that can annoy both of you.

When performed correctly this technique actually puts less wear and tear on the transmission, making it mechanically safer than

engaging all the extra clutch parts. Keep in mind that this assumes a full engine load. At small throttle openings, there is no need for fast upshifts so you should shift as normal.

It won’t take that long to get proficient at upshifting, but downshifting turns out to be the single most difficult technique we teach in our Total Control Advanced Riding Clinics. The goal is to match the engine speed to the rear wheel speed when downshifting. This technique is called “rev-matching” or “blipping” and offers two advantages: 1) the engine speed will be in its powerband in the lower gear if you need to all of a sudden accelerate and 2) during deceleration the rear tire will not chatter or loose traction while downshifting.

Downshifting by just pulling in the clutch, downshifting the transmission and letting out the clutch causes the engine to have to

“catch up” to the speed of the rear wheel. This resistance causes the tire to break traction, puts undue wear on the clutch and makes the motorcycle jerk as the clutch is let out.

Some modern day sportbikes have what’s called a slipper clutch, or back-torque limiting clutch. A slipper clutch is designed to

have the clutch plates freewheel until the engine speed catches up with the wheel speed. I look at slipper clutches the same way

as I do quickshifters and ABS. They are all great technology to have, but if you don’t understand what they’re doing, it can be

dangerous when you change to bikes that don’t have that feature. In other words, you don’t want to completely rely on the technology. It is there just in case, not as a replacement for good technique.

Having said that, here are two steps necessary to downshift properly. The first one is complicated, and the second one is more complicated! Starting with Step 1, you want to simultaneously roll off the throttle and apply the front brake. Step 2 requires simultaneously maintaining even pressure on the brake while quickly rolling on and off the throttle, quickly engaging and disengaging the clutch, while at the same time quickly downshifting. While this sounds a little overwhelming at first, with some practice at speed, it will eventually become as natural as using the clutch. Try 4th to 3rd or 3rd to 2nd before trying 2nd to 1st. Happy shifting!